Establishing Indigenous Protected Areas for Future Generations in the Face of Extractive Capitalism

By Megan Youdelis, Justine Townsend, Jonaki Bhattacharyya and Faisal Moola

July 14, 2021

This blog post is based on our co-authored article, titled “Decolonial Conservation: Establishing Indigenous Protected Areas for Future Generations in the Face of Extractive Capitalism”, in review in the Journal of Political Ecology. Authors include Megan Youdelis (University of Guelph), Justine Townsend (University of Guelph), Jonaki Bhattacharyya (University of Victoria), Faisal Moola (University of Guelph), and J.B. Fobister (Grassy Narrows First Nation). Special thanks to former Chiefs Russel Myers Ross (Yunesit’in Government) and Marilyn Baptiste (Xeni Gwet’in First Nations Government) who reviewed drafts and whose insight and expertise were instrumental to telling the story of Dasiqox-Nexwagwez?an

The Ontario government, under Premier Doug Ford, has recently come under fire for allowing a surge of gold mining claims in Grassy Narrows First Nation’s territory without their consent. In addition to the damage done by decades of clearcut logging, Grassy Narrows’ territory has been poisoned by mercury for almost 60 years, after a pulp and paper mill dumped 10 tonnes of the toxin into the Wabigoon River in the 1960s. To date, neither the company nor the provincial or federal governments have cleaned up this disaster.

Instead of using the $187 million trust fund earmarked to clean up the mercury poison, the government has allowed 4,000 gold mining claims within the nation’s declared Indigenous Protected and Conserved Area (IPCA). If developed, these claims would threaten Grassy Narrows First Nations’ rights to their lands and waters and would further undermine the health, culture, and livelihoods of its people.

This shameful example of environmental injustice points to a broader paradox in Canadian conservation: Indigenous-led conservation is often supported in theory, but undermined in practice. Canadian federal, provincial and territorial government agencies voice support for IPCAs and intend to count them toward their international conservation commitments. However, other agencies, ministries, and actors within those same Crown governments often threaten IPCAs by awarding tenures to extractive industries (eg. mining, logging, oil and gas, etc.) without the consent of, or ensuring benefits to, local Indigenous peoples.

The Promise and Paradox of Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas

IPCAs represent a decolonial alternative to conventional state-led conservation, which historically displaced Indigenous peoples from their territories. Unfortunately, in some instances conservation efforts are still displacing Indigenous peoples from their relationships with lands and waters. Despite this, Indigenous peoples still protect the majority of the world’s remaining biodiversity. Indigenous-led conservation elevates Indigenous laws, rights and responsibilities to lands and waters, and is crucial to protecting both social and ecological vitality. Importantly, in Canada and other settler states, IPCAs can facilitate biological and cultural conservation in the spirit of true reconciliation and repair.

Grassy Narrows members at anti-logging blockade. Photo: David P Ball.

However, many proposed or declared IPCAs are overlain with tenures (mining claims, leases, prospecting permits and/or exploration licenses) from resource extraction industries. While IPCAs are established for many reasons, many nations declare IPCAs to assert alternative visions for their lands and waters in the face of destructive colonial and capitalist practices.

Gassy Narrows Indigenous Sovereignty and Protected Area (Ontario, Treaty 3) and Dasiqox-Nexwagwez?an (a Tribal Park in non-treatied Tsilhqot’in territory, B.C.) are two such cases, among others. To delay unwanted development, Indigenous nations in both cases have at times formed blockades. It is unconscionable that they would need to engage in this form of land defence in a country that has signed onto UNDRIP, with its principle of free, prior, and informed consent.

Grassy Narrows Indigenous Sovereignty and Protected Area

Grassy Narrows First Nation has been fighting for environmental justice for over a century. In the 1920s, the construction of a hydroelectric dam flooded Grassy Narrows, destroying burial grounds and wild rice harvesting areas. As the 1962 mercury spill has yet to be cleaned up, Grassy Narrows residents continue to suffer from physical pain, tremors, impaired sight, speech and hearing, loss of muscle coordination and premature death as a result of exposure to mercury.

When clearcut logging began accelerating in their territory in the 1990s, Grassy residents decided to take action. Led by the Grassy Narrows Environmental Group, the nation began the longest-standing Indigenous-led blockade in Canadian history in 2002. Along with various legal challenges and boycott campaigns organized with Non-Governmental Organization (NGO) partners, they successfully forced the logging company, Abitibi-Bowater, to relinquish their license in 2008. However, there was a possibility that other companies could pick up the license, and Grassy Narrows and its partners understood that further action was necessary.

In 2015, they held a community referendum where 75 percent voted to ban industrial logging entirely. This led to the 2018 Land Declaration, wherein the Grassy Narrows First Nation government declared their entire Traditional land Use Area an Indigenous Sovereignty and Protected Area (ISPA; a form of IPCA). Grassy decided to use the term ISPA to highlight the fact that stewarding their territory is their sovereign right.

Map 1.0: Willow (2012: 2)

The Land Declaration bans all industrial activity within the ISPA and outlines Grassy’s vision for an Indigenous-led conservation economy. Grassy declared the ISPA in part to try to negotiate removing their territory from the area available for logging or other extractive licenses. The ISPA was therefore the culmination of a long struggle for land protection in the face of resource extraction.

While their ISPA is supported by the federal government through the Challenge Fund program, the provincial government in Ontario is continuing to undermine the ISPA as well as the rights and governance of Grassy Narrows First Nations. The communities are now facing another major fight to protect their territory from gold mining. This highlights the tensions between Canada's development and reconciliation agendas. We contend that the Ontario government and mining companies must respect Grassy Narrows’ Land Declaration, and abandon any claim staking and mining exploration within its declared ISPA.

Dasiqox-Nexwagwez?an

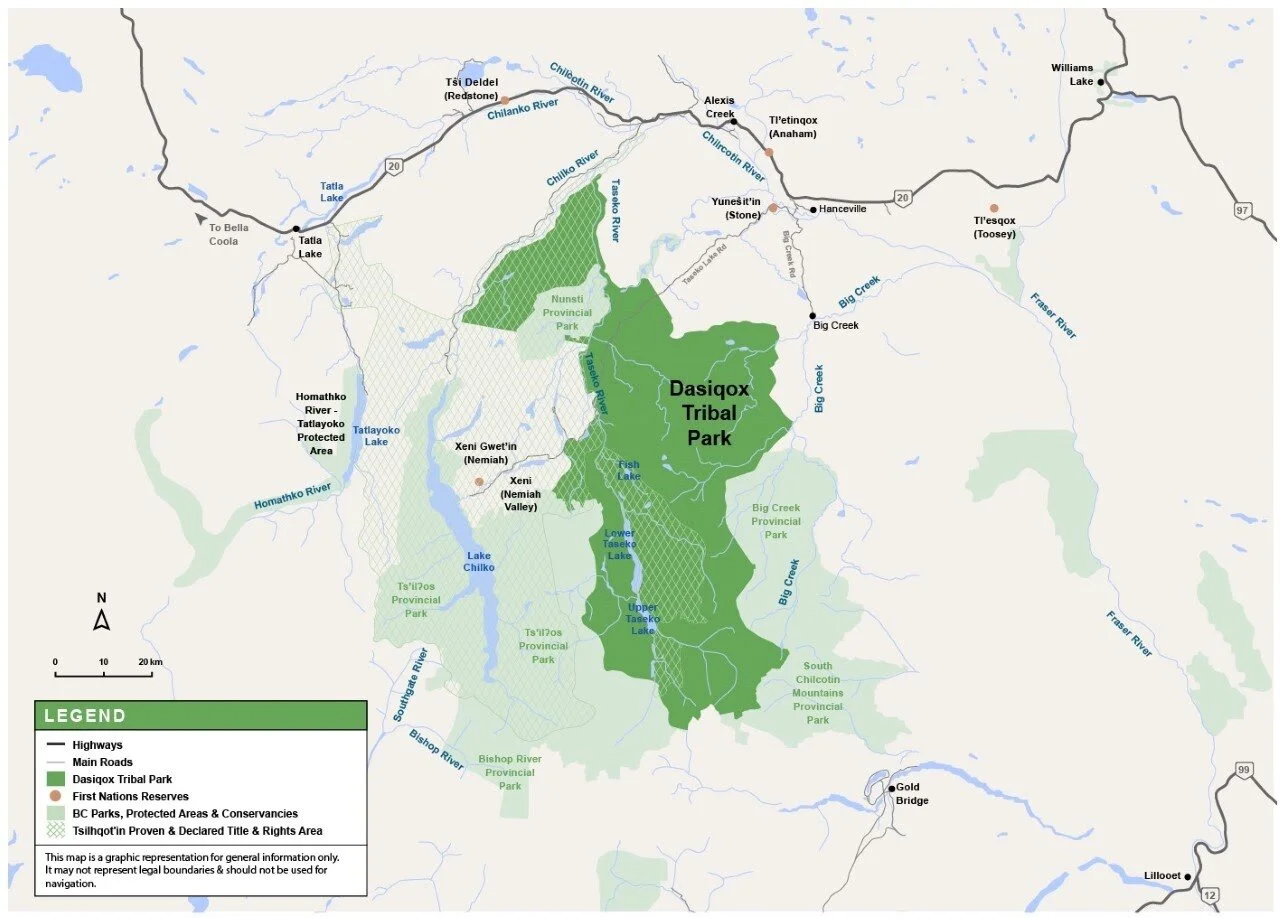

Dasiqox-Nexwagwez?an in Tsilhqot’in territory in B.C. similarly highlights the importance of respecting Indigenous jurisdiction in IPCAs. The Xeni Gwet’in First Nations Government, the Yunesit’in Government, and Tsilhqot'in National Government declared Dasiqox-Nexwagwez?an in large part in response to decades of pressures from mining and logging industries throughout their territories. Meaning “there for us,” the vision for Dasiqox-Nexwagwez?an is based on the three pillars of cultural revitalization, local economic development, and ecological protection.

Members of the Tsilhqot’in Nation at Teztan Biny (Fish Lake), where they have actively opposed the development of an open pit gold-copper mine for over 30 years.

Photo: Tsilhqot’in National Government.

Another major impetus was the Supreme Court of Canada’s landmark ruling in 2014 that recognized a portion of Tsilhqot’in title lands and affirmed their rights in a larger area around the title lands. Dasiqox-Nexwagwez?an is primarily outside but adjacent to the approximately 1,800km2 where the Supreme Court recognized Tsilhqot’in title.

In 1989, Xeni Gwet’in First Nation issued the Nemiah Declaration in response to the intensification of ranching, logging and mining throughout the 20th century. The declaration banned commercial logging and mining activity as well as flooding and dam construction. After initiating a roadblock to protect the remaining unlogged portion of their territory, the communities launched a series of court battles that affirmed their rights to hunt and trap within the entirety of their claim area.

In addition to protecting their lands and waters from logging, the Tsilhqot’in were concurrently resisting the construction of the Prosperity Gold-Copper Mine proposed by Taseko Mines Ltd. The proposed mine fell within a sensitive and culturally significant part of their territory around Teztan Biny (Fish Lake) and Nabas. Despite being twice rejected by the federal government through the Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency’s review process, which recognized that the mine would have adverse impacts ecologically and culturally, the pressure continued.

In their final days of office in 2017, the provincial government in B.C. issued a permit for Taseko Mines Ltd. to conduct ‘exploration’. The province issued this permit even though the proposal could not proceed without federal approval, which was still lacking. In addition to launching further legal challenges, Tsilhqot’in members again blocked the mining company from entering the territory and Dasiqox-Nexwagwez?an in 2019.

The Supreme Court of Canada ruled in 2020 that Taseko Mines could not appeal the federal government’s double rejection of their proposal. But in 2021, BC’s Chief Executive Assessment Officer (CEAO) granted yet another extension to Taskeo's permit, apparently to “allow for a dialogue[...] aimed at exploring a long-term resolution of the issues" (see this WCEL blog for a full discussion). As Taseko’s mineral tenures do not expire until 2035, the potential of a mining project still looms, particularly since Dasiqox-Nexwagwez?an is not formally protected under Crown legislation.

The unresolved mineral tenures were reportedly a significant contributing factor in Canada’s decision not to fund Dasiqox-Nexwagwez?an. Dasiqox’s application for federal Challenge Funds was unsuccessful. Nevertheless, the initiative continues to support cultural learning and events, conduct applied research, steward and restore important areas, and engage Tsilhqot’in elders and community members in these efforts.

Addressing the Paradox

Indigenous nations, governments, and communities have been fighting to build a path to a more promising future for all. Dasiqox-Nexwagwez?an and Grassy Narrows ISPA are two such examples. However, Crown government agencies need to be true partners and not just talk the talk, but walk the walk.

If Indigenous jurisdiction and visions for the lands and waters are upheld, IPCAs may offer glimpses into how alternative sustainable land management might work. If adequately recognized and supported by federal, provincial, and territorial governments, IPCAs could be living, breathing processes of reconciliation — models for new relationships among settler society and Indigenous peoples, and among all peoples who live with the same lands and waters.