Peatlands: Vital for Carbon Storage and Stewardship

By Justina Ray and Meg Southee, Wildlife Conservation Society Canada

August 5, 2020

The CRP is pleased to present this blog post by one of our partner organizations, Wildlife Conservation Society Canada. Learn about their work here: https://www.wcscanada.org/Our-work-to-save-wildlife.aspx

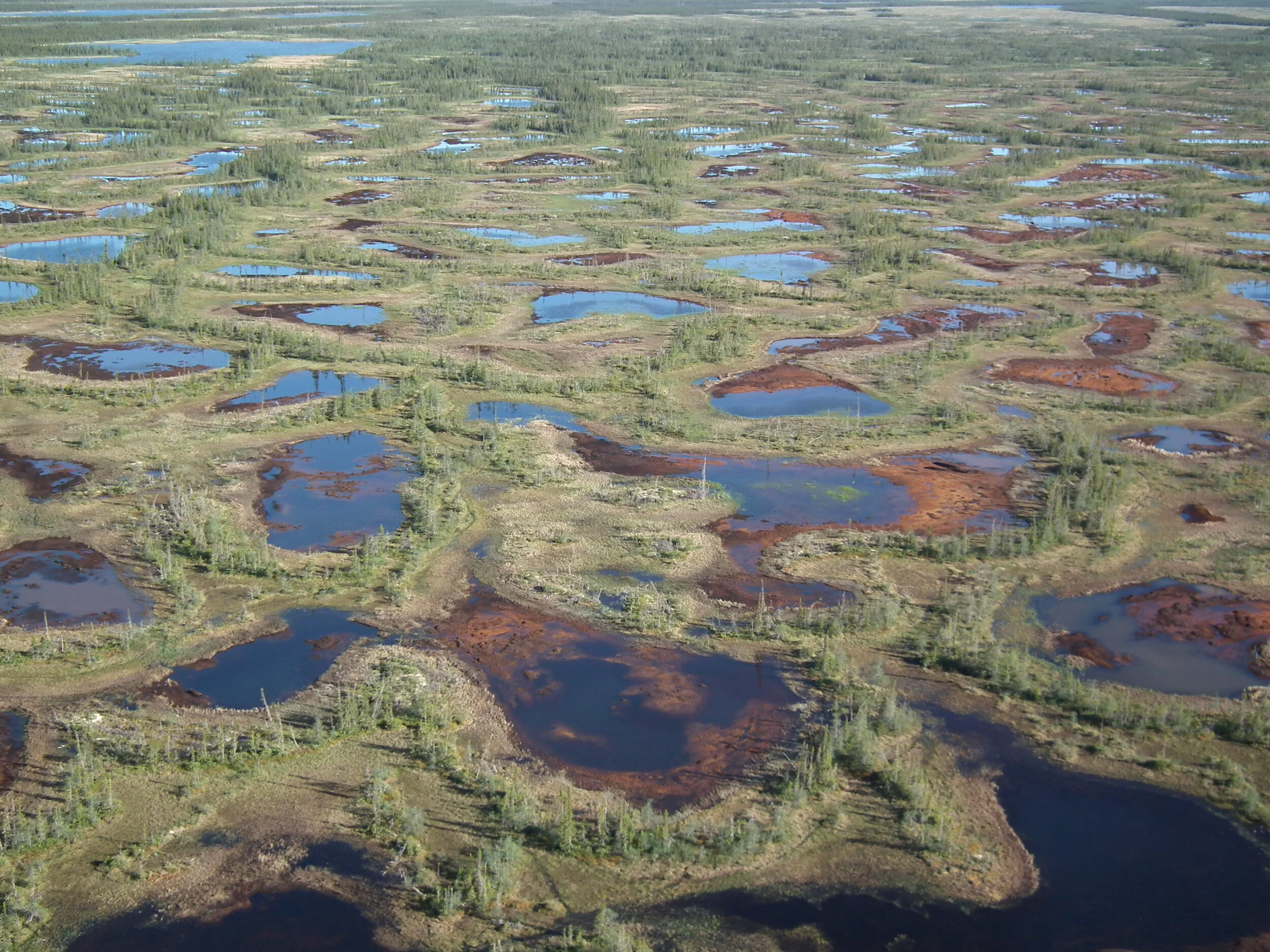

Peatlands are finally getting some overdue respect. A type of wetland, these unique ecosystems are particularly noteworthy because of their unusually deep organic soils formed by thousands of years of waterlogged decaying plants and mosses. While they exist in all parts of Canada, some of the largest peatland complexes in the world are in northern Canada. Peatlands are a vital resource – a filter for ensuring rivers run clean, a haven for wildlife and, as we now increasingly appreciate, a huge storehouse for carbon.

Image of peat bog. Photo credit: Mike Oldham

Canadian Boreal forest and peatlands. Map Credit: WCS Canada/Meg Southee

Understanding the importance of peatlands as a carbon sink has become increasingly vital as we grapple with climate change. One of us had the privilege of participating in a workshop on nature-based solutions put on by the Conservation through Reconciliation Partnership (CRP) about a year ago. The workshop focused on the linkage between Indigenous-led conservation and carbon stewardship in Canada. That got us thinking about how little most Canadians know about peatlands and how our current carbon accounting systems fail to properly consider and value these areas.

We then began to develop a “story map” about the value of peatlands, their role in carbon storage, and how they are being affected by climate change and industrial development. The result is a visual narrative that guides viewers through how peatlands function, how they may be affected by climate change and what happens when roads, mines or other developments are built through or within them.

Peatlands are a big piece of Canada’s geography – covering over 1.1 million km² or approximately 12% of Canada’s total land area. They are also carbon rich: one square metre of peatland in northern Canada has around five times the amount of carbon found in one square metre of tropical rainforest in the Amazon. These huge amounts of carbon stored below ground in northern peatlands can be locked in for centuries – up to 7,000 years. By comparison, rainforests mostly store carbon above ground and turn their carbon over in about 100 to 500 years.

Credit: Lucy Poley

So stewarding these areas is hugely important and it is Indigenous peoples who have been the stewards of these often remote areas from time immemorial. Their job is getting a lot more complicated, however, thanks to the combined pressure of climate change and ever-expanding resource development. Climate change may dry out peatlands and lead to increased wild fires, releasing ancient carbon into the atmosphere. Industrial development, including roads, transmission lines and hydro dams, can also lead to drying out or flooding, again causing carbon to be released as well as directly destroying both individual areas and severing connections between areas.

That’s why, as articulated in a recent FACETS article by members of the CRP, it is critical to find ways for the Indigenous stewards of these areas to directly benefit from their stewardship of carbon and other services and why the CRP workshop was such a valuable opportunity to begin discussing how this might occur. Similarly, integrating peatland storage into Canada’s official carbon accounting models and policies will help greatly with ensuring we recognize the value of proper stewardship in these areas.

We have much to gain from properly caring for peatlands and a lot to lose from poorly planned development. Proposals for major mining activities and roads in Ontario’s Ring of Fire within the homelands of Mushkegowuk First Nations, for example, need to be examined through the lens of their impact on peatlands and their carbon storage, water filtration, and wildlife support functions before we start building roads or mines. The Hudson Bay Lowlands region, for example, contains some of the last undammed rivers of North America, which transport large quantities of nutrients and organic material to the coast and make the Bay’s coastal zone very productive for biodiversity.

Simply carrying on with business as usual in these highly sensitive areas could quickly compromise these irreplaceable values and unlock vast amounts of carbon – the last thing our atmosphere needs right now. As we have seen with the current COVID-19 crisis, disturbing wild areas can have serious unintended consequences. Simply stated, the health of these places is tied to our health and well-being.